PLEASE NOTE: We have received several emails disputing the POW account in this story, based on not being able to find Carl Bennett's name in the POW directory. His name does not appear there because he was only in captivity for 3 days, and never reached a POW camp. He escaped while still enroute. We have a number of troopers who served with Carl Bennett and were present when the POW event took place. They have verified his account. We fully agree that those making false claims should be exposed. However, it is also important not to inflict further wounds by falsely accusing those who have indeed served.

This story was originally published in the Forsyth Herald newspaper (near Atlanta, Ga) on Nov. 10, 1999, in Vol. 2, No 2

Editor and story author: James Budd - an attempt has been made to request permission to republish the story here, but the web address given, http://www.appnews.com, is no longer in service. If you have information on how to contact James Budd or the management of the Forsyth Herald, please forward to the webmaster.Webmaster

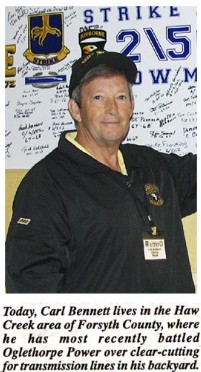

Forsyth County resident Carl Bennett doesn't need the formal observance of Veterans Day Nov. 11 to remind him of his personal experiences and those of other young Americans three decades ago in the distant jungles of Southeast Asia.

Bennett, now 54, doesn't talk much about his activities during the war. Indeed, some of his activities were classified and remain so. He was in and out of Southeast Asia for nearly a decade during the Vietnam War Era.

But with some prying, he will talk reluctantly about a few of his experiences. They are as colorful as they are painful.

In September 1965 Bennett was captured by the Viet Cong in the Central Highlands when a joint mission between the Marines and the Army went afoul.

He escaped after four days of brutal captivity as the VC were marching him and two other Americans north through the jungle to Hanoi.

According to Bennett, American intelligence had indicated the Viet Cong were using a valley near the An-Khe Pass for training and other operations.

"Our mission was to land at the head of this valley and sweep it," said Bennett. "It was a joint operation between the Marines and the Army. It was screwed up. We landed in the middle of the valley right on Charlies' machine gun range. They knocked six choppers out of the air in less than 20 minutes.

"All that night we had to have flares from C-130s drop," he said. "We were surrounded. We were supposed to have artillery support, but we were just out of range. We were catching 47 kinds of hell up there."

The pinned down Americans were spread out in a checkerboard pattern, which apparently confused the enemy and made them wary of attempting to overrun the survivors that night.

The VC weren't sure of the strength or concentration of the Americans, he said.

The next day, the unit was told to sweep the area. About 6 p.m., Bennett said they were ambushed.

"I had 12 VC looking at me - why they didn't shoot me I'll never know," he said.

For the next three days, Bennett and a "couple of Air Force guys" were marching north by the enemy during the day.

At night, the POWs had to dig head-deep holes, get in and the VC would bury the captives up to their shoulders. A basket would be placed over their heads. During the night, the POWs were used as latrines by the VC, he said.

"I wasn't going to Hanoi," Bennett recalls firmly.

On the fourth night, as he was digging his "spider hole," Bennett noticed his digging was having a hypnotic effect on his guard and it almost seemed as if the man was nodding off.

"We had gone a long way that day and he was tired," said Bennett.

Bennett took advantage of the situation and bashed the guard in his face with an entrenching tool and grabbed his Russian-made AK-47.

Bennett quietly says he things the blow to the guard was fatal.

"It seemed like I ran for hours and then stopped when I couldn't run anymore," he said. "I wanted to put as much distance between us as possible."

However, Bennett realized he had to go back to see if he could help the American airmen who were being held.

"I decided to move back in from another direction," said Bennett.

When he arrived back at the area, the VC, apparently spooked by Bennett's escape had moved the airmen and were preparing to move out that night.

"There was nothing I could do," said Bennett, his voice trailing off.

For the next several nights Bennett went downstream, eating ants and other bugs and holing up during the day.

"We were told to get to a stream and go downstream since they run from north to south,' said Bennett.

Bennett had to dodge the VC - and the bamboo vipers.

"They are about a foot or foot-and-a-half long," he said. "It's a two-step snake. Once you're bitten all you'll take is two steps."

"In Vietnam things were different. Cows could be as big as dogs, but they had centipedes that were eight or 12 inches long."

Bennett said he had several close calls with the VC during his escape.

He was floating in a river one night in a collection of debris he had gathered to conceal his travel. At one point he mistakenly came within four feet of a dugout canoe manned by VC. He silently sank underwater as long as he could and when he surfaced they were farther away and hadn't spotted him.

Bennett eventually got to just west of DaNang and the DMZ, but he didn't know the password to get to the other side. Bennett realized he could be gunned down by friendly fire if he wasn't careful.

"I figured I would have a better chance of not getting killed by staying in the river," said Bennett.

About the sixth night of his ordeal he came upon a U.S. Navy patrol boat. The boat's .50 caliber got off a short round at him from about 50 yards away before the ammo bearer stopped the gunner.

"They got me out of the water and took me to port," he said.

After questioning by G-2 (intelligence) he was sent back to his until and back into combat.

"I was a little malnourished, but mentally I was great because I was with people that weren't trying to kill me," he said.

Not long after his capture, Bennett and his unit were about to wrap up a one-year tour. "You only go there for a year at a time," said Bennett.

Bennett and most of his unit were eligible to go home for a while when they were asked if they wanted to volunteer to rescue some soldiers bogged down in a place called "Happy Valley" in the Central Highlands.

"We didn't have to go back, but we all went [to help]," said Bennett. "I got hit. I was along at the right place at the wrong time."

That was just one time Bennett was wounded. In all, Bennett received five Purple Hearts. Bennett also made trips to Laos, trained Thailand's "Queen Cobras" for combat and made other forays that are classified.

What are his thoughts about Vietnam?

"The only regret I have is a lot of people - good people - died over there that didn't have to," he said. "When we arrived over there we were told we couldn't shoot at anything unless we physically saw them fire a weapon. We couldn't win with our hands tied. The body count became the most important thing. We weren't there to win the war."

Other thoughts?

"I think one of the greatest things that came out of it is the color of a person's skin didn't matter - you were constantly looking out for one another," said Bennett. "It's unfortunate we can't have that feeling in peace time. That thought sticks with me."